In this final installment of our March podcast villain series, we decided to end with a character who has been interpreted in more ways than almost any other: Count Dracula.

Meaghan and Arthur dove into this rich, multifaceted figure who has stood the test of time, appearing in literature, theater, film, television, comics, and even ballet. While Dracula is far from the first fictional villain, his enduring presence makes him one of the most iconic.

Across generations, the character has been portrayed in so many forms that it almost becomes impossible to count. So we took on the challenge of tracing Dracula’s origins, his evolution across media, and our own personal favorites from his cinematic portrayals.

Note

The following is an editorialized transcript of our weekly literary podcast. If you would like to listen to the podcast, click the play button above orlisten on your favorite platform with the links below.

The Roots of Dracula

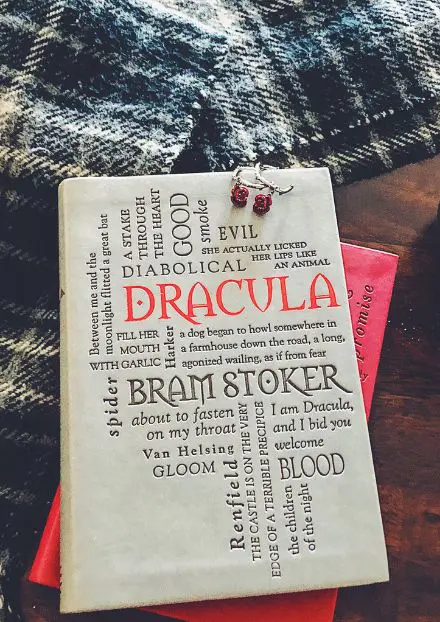

We began by introducing listeners to the original story of Dracula, the novel published in 1897 by Irish author Bram Stoker. The novel is set up in an epistolary format, meaning it’s told through letters, journal entries, telegrams, and various documents — a storytelling method that adds a documentary-like authenticity to the supernatural tale.

Much of it was written while Stoker stayed in Whitby, England, a location that eventually inspired part of the book’s setting. In the story, Jonathan Harker travels to Transylvania to help a mysterious count named Dracula purchase property in England. Things spiral into horror as Dracula makes his way to London, bringing with him death and chaos.

As we discussed, there’s a longstanding debate about Dracula’s real-life inspiration. The common theory connects him to Vlad the Impaler, a ruthless 15th-century ruler known for his violent methods. There’s also speculation around Hungarian countess Elizabeth Bathory, infamous for allegedly bathing in the blood of young girls. However, newer scholarship suggests Stoker might have chosen the name “Dracula” simply because he misunderstood it to mean “devil” in Romanian.

We also touched on the thematic weight of Dracula’s character – how, especially during the Victorian era, he symbolized temptation, corruption, foreignness, and disease. His ability to lure women into his power and feed on them while they remained semi-willing created a metaphorical blend of sexuality, danger, and the fear of the “other” that resonated with readers of the time.

Enjoying this article?

Subscribe to our weekly newsletterDracula on the Screen: From Shadows to Sound

We explored how Dracula’s story was first visualized in cinema, starting with the silent film Nosferatu (1922), a German adaptation that changed character names to avoid copyright issues.

Despite efforts by Stoker’s widow to have all copies destroyed, a few prints survived, and the film became a cult classic. Nosferatu laid the groundwork for what would become the Dracula visual standard — looming figures, haunting silhouettes, and unsettling stillness.

We then examined the 1931 Dracula film starring Bela Lugosi, the first officially licensed screen adaptation. Lugosi’s performance shaped the image of Dracula in popular culture: the accent, the cape, the stare.

We learned that Lugosi performed the role phonetically, not speaking English fluently, which added to the eerie stillness of his portrayal. Interestingly, a Spanish-language version was filmed simultaneously using the same sets, which many critics consider to be superior in certain technical aspects.

Dracula became the foundation for Universal Studios’ “monster movie” identity, alongside Frankenstein, The Mummy, and The Wolfman. These films established a shared aesthetic that would be drawn upon for decades.

RelatedVillains Who Became Legendary In Adaptations

Waves of Interpretation: Gothic Horror to Sexy Vampires

From the 1950s through the 1970s, we saw a gothic revival of Dracula through Hammer Horror films, most prominently featuring Christopher Lee. We both appreciated Lee’s version — a charismatic, regal Dracula — and talked about how he portrayed the character in seven different Hammer films. In some of those, he even refused to speak if he found the lines poorly written, creating a more silent, menacing figure.

The 1970s also brought in more playful and unconventional interpretations, like Blacula, a Blaxploitation reimagining. We highlighted how William Marshall’s portrayal introduced a sophisticated, socially aware Dracula figure who challenged racial themes head-on. There was also Frank Langella’s Dracula, which leaned heavily into romantic seduction, further evolving the character from monster to tragic anti-hero.

Then came the 1992 film Bram Stoker’s Dracula by Francis Ford Coppola, starring Gary Oldman, Keanu Reeves, and Winona Ryder. While visually rich and ambitious in scope, we felt it was uneven — a mix of great performances and questionable choices, particularly with casting and pacing.

RelatedFrom Dracula to Gone Girl: What Truly Makes a Villain Iconic?

Modern Spins and Reinvention

We also explored how Dracula has fared in the 21st century. In the 2000s, the character began to be molded in more experimental or comedic directions. We discussed Dracula 2000, which offered a wildly original origin story — portraying Dracula as Judas Iscariot, cursed with immortality for betraying Jesus. Despite the film’s overall mediocrity, we admired the creativity of that take.

Then, there was Dracula Untold (2014), a more action-oriented approach that reconnected Dracula to Vlad the Impaler. While not universally loved, we found it entertaining and appreciated its attempt to craft a distinct backstory. Meanwhile, the 2020 BBC/Netflix miniseries Dracula starring Claes Bang impressed both of us deeply. We praised it as one of the most creative and engaging portrayals in recent memory, successfully blending horror, humor, and charisma.

We also talked about recent comedic takes like Renfield (2023), with Nicolas Cage going full camp as Dracula. Cage’s performance stood out despite the film’s weaknesses — we both agreed he injected new life into a familiar character. Additionally, animated versions like Hotel Transylvania took Dracula in a fully comedic, family-friendly direction.

Cultural Impact and Curiosities

Beyond film, Dracula has appeared across multiple mediums. We were fascinated to learn that he had a run in Marvel comics in the 1970s in Tomb of Dracula, which also introduced Blade. There were radio adaptations, most notably one with Orson Welles, and even ballet productions like Dracula: Pages from a Virgin’s Diary, combining gothic horror with Canadian ballet.

We included several TV portrayals in our honorable mentions, such as the Buffy the Vampire Slayer episode “Buffy vs. Dracula,” and a Supernatural episode featuring a Dracula-inspired shapeshifter. These versions brought humor and novelty to the character, continuing his evolution into satire and pastiche.

And, of course, we couldn’t forget the Count from Sesame Street — likely the only Dracula interpretation who’s never been evil, only educational.

Related10 Iconic Fantasy Books Villains Readers Love to Hate

Our Personal Rankings and Final Thoughts

We each compiled a top-five ranking of our favorite portrayals of Dracula. While our picks varied in the lower ranks — with shoutouts to Nosferatu, Blacula, Dracula Untold, Nicolas Cage’s Renfield Dracula, and the 1931 Bela Lugosi version — we both agreed that Claes Bang’s portrayal in the 2020 miniseries was number one. His performance captured a blend of menace, charm, and unpredictability that felt refreshing and memorable.

As we wrapped up the episode, we reflected on how Dracula, as a character, has endured through decades because of his adaptability. Whether terrifying, seductive, tragic, or hilarious, Dracula continues to evolve with the times. From Victorian fears to modern humor, he offers creators endless possibilities to reimagine what a vampire — and a villain — can be.

We’re wrapping up villain month with this tribute, but we’re excited to start a brand new theme next week. Dracula might be going back to his coffin for now, but he’ll certainly rise again.